Hacking the Medium Partner Program

This article details the journey and methodology behind how my name was added to humans.txt after reporting my first bug bounty—a severity 2 vulnerability. I am sharing this because I have always been interested in the process of discovering security vulnerabilities. The vulnerability itself is remarkably simple to exploit; technical details are provided at the end of this article.

Background

I initially intended to write an article analyzing how much of the $5 monthly membership fee is distributed to writers through the Medium Partner Program. My plan was to test various interactions—such as reading duration, highlighting text, and clapping—to determine their effect on a writer’s compensation. Operating on a limited budget, I used a single “control” account for all testing. I had designed over 20 different test scenarios, but since Medium Partner Program earnings are calculated daily, I was limited to testing one scenario per day. Consequently, I sought to automate the process. I began by exploring the Chrome Developer Tools to analyze how data is transmitted to medium.com to see if automation was feasible.

I started by selectively blocking requests to specific URL paths that I suspected were transmitting the metrics used to calculate earnings. After significant trial and error, I discovered that requests to medium.com/_/batch were responsible for transmitting the data used to calculate Partner Program earnings.

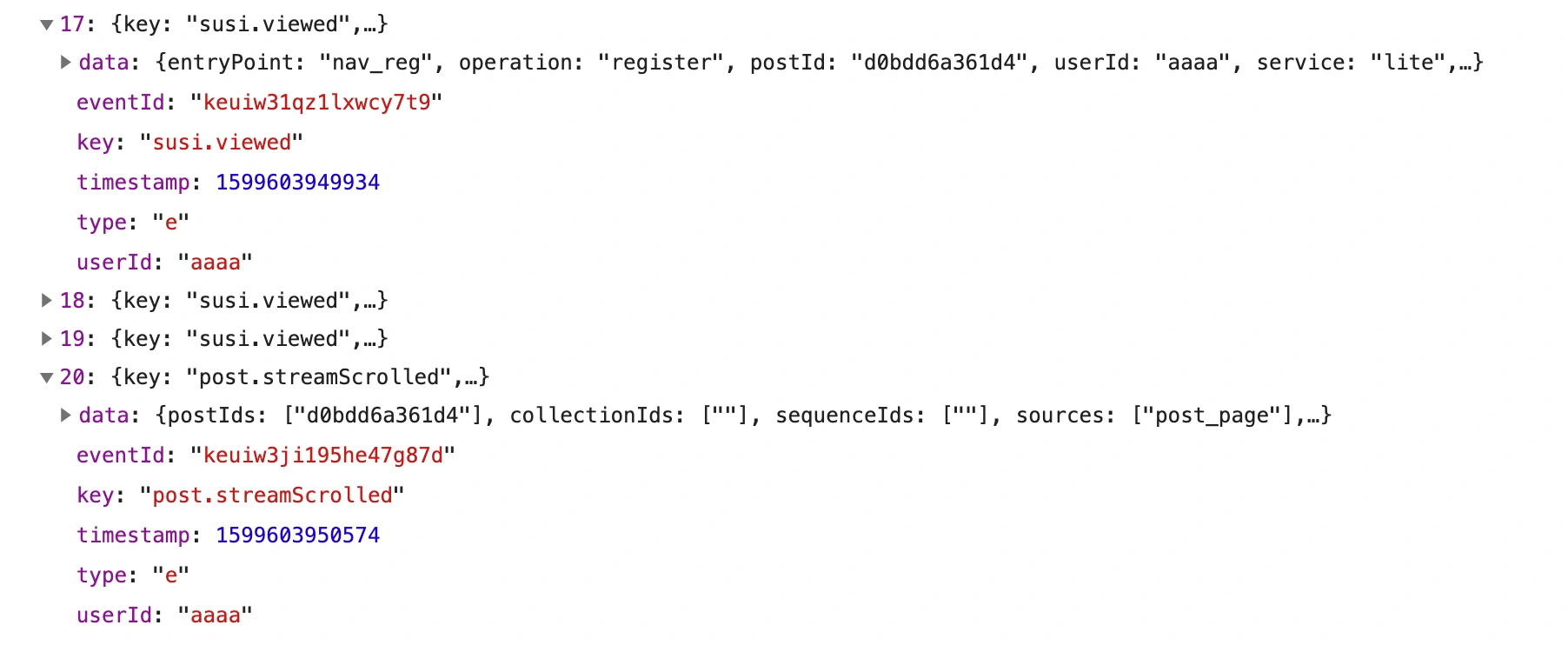

Initially, I could not decipher much of the data transmitted to the medium.com/_/batch

endpoint. My strategy was to replay the requests made to this endpoint, modifying only the timestamp data to match the time of the replay (which could be days after the initial capture).

To avoid hardcoding cookies into my Python script, I attempted to clear my browser cookies after loading the webpage. Surprisingly, even without any cookies present, I was still able to generate Partner Program earnings. I then analyzed the request JSON data to see if I could generate all the POST request data required for a session of arbitrary duration at once (essentially a batch of page scroll events) and transmit it in a single request. This would have allowed me to automate testing sessions of various lengths. Unfortunately, this approach did not work.

I originally hypothesized that the server validated the transmission time to prevent retroactive or future earnings generation. However, after further experimentation with correct timing and varied payloads, I concluded that the eventId in the JSON payload is likely a hash containing the userId and the date of the page view. There appears to be a pattern in the eventIds, where the first four characters are identical for requests from the same userId on the same day. Due to code obfuscation, I was unable to reverse-engineer the exact generation method.

Vulnerability Discovery

It was at this point I realized that aside from the userId included in every JSON object in the request payload, nothing unique to the user was being transmitted to medium.com/_/batch

. Modifying the userId alone did not allow me to generate earnings. (Note that the endpoint always responds with "success": true regardless of the request content.) I proceeded with trial and error to understand the authentication mechanism. I suspected that my inability to compute valid eventIds was the issue.

I initially attempted to use a find-and-replace on the website’s main HTML file to swap my current userId with that of another paid account I owned, then invoked the initialization JavaScript functions. This failed due to the aggressive code obfuscation on medium.com. My next plan was to inspect and modify my own traffic using MITMProxy, a Python library, to intercept and replace my userId with a target userId while the data was in transit.

The Breakthrough

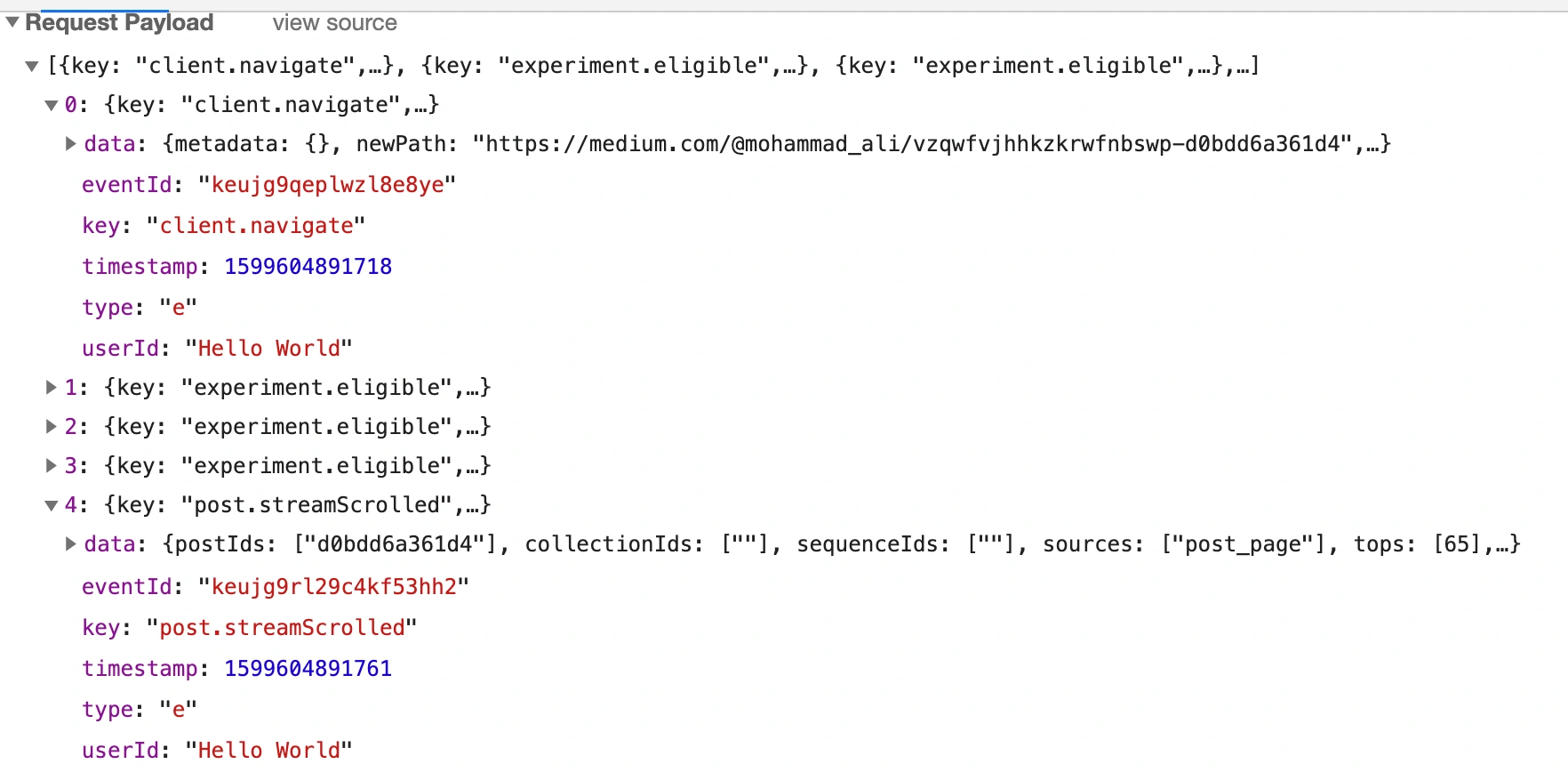

I decided to try modifying the UID cookie value in the request to the main HTML page of an article. Significantly, medium.com

embedded the UID cookie value into the webpage as JSON data before validating that the session cookie and UID cookie represented a valid logged-in session. Although the webpage correctly identified my UID/session cookie as invalid, it still embedded the UID data from the request cookie into the webpage. In the response, it sent back Set-Cookie headers with a new session UID starting with “lo_”. Consequently, whatever UID cookie value was used for the main page request, all subsequent batch requests (to the API endpoint) used that value as the “userId”.

Here is an example where I changed the userId to “Hello World”:

I also discovered that retrieving other users’ userIds is trivial. By navigating to a user’s profile and searching for "{\"id\":" in the page source, the userId can be found. For instance, the Netflix Tech Blog

userId is "c3aeaf49d8a4" (these userIds are intended to be public).

Therefore, when I changed my UID cookie to that of a paying user and loaded an article I had written, Medium transmitted data to its /_/batch

endpoint using the target’s userId. If I proceeded to read the article, it generated revenue for the writer. Medium accepted the userId values without validating them against the session.

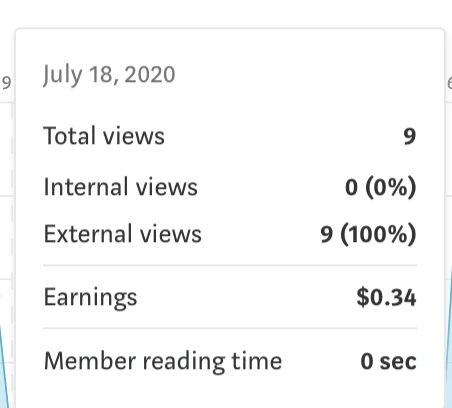

I successfully generated 34 cents by impersonating approximately 10 people in a single day. I limited my testing to avoid any perception of malicious intent and reported the bug through their bug bounty program immediately.

Conclusion

In conclusion, I discovered that member reading time appears to have no correlation with Partner Program earnings.

I observed that Medium.com embeds any userId cookie value transmitted to them into their webpage.

Crucially, I found that the Medium Partner Program endpoint does not verify that the user has a valid logged-in session, but instead accepts userIds without validation.

It remains unknown if I was the first to discover this vulnerability. It is possible that Medium Partner Program writers could have been deprived of revenue if this vulnerability was exploited by others to manipulate the earnings distribution.