An Introduction to Horizontal Asymptotes

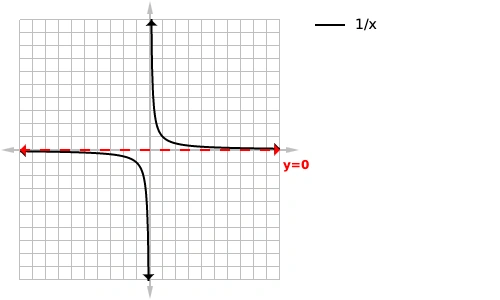

Horizontal Asymptotes (often abbreviated to H.A.) are horizontal lines that a function will approach and become infinitesimally close to, but will never touch, as the function approaches either positive or negative infinity.

Three general types of asymptotes exist: vertical ones, horizontal ones, and oblique ones (also commonly called slant asymptotes). In this tutorial we will be focusing only on horizontal asymptotes as they are the easiest to determine. The equation for a horizontal asymptote will be a horizontal line.

Definition

A horizontal asymptote is a horizontal line (a y value) that the function will approach as x approaches positive and/or negative infinity.

Horizontal vs Vertical Asymptotes

Horizontal asymptotes have some clear differences from vertical asymptotes. It is okay for your function to pass through a horizontal asymptote a fixed number of times. Furthermore, a function can only have a maximum of 2 horizontal asymptotes: one as x approaches positive infinity and one as x approaches negative infinity. Horizontal asymptotes are also more commonly written with limits because in theory, when x is infinitely large, it will touch our asymptote.

Finding Horizontal Asymptotes

Horizontal asymptotes, unlike vertical ones, are very easy to find. That’s because we always know where horizontal asymptotes may occur—if they are to exist, they must occur at positive and/or negative infinity.

So the easiest way to solve for one would be to plug in 2 very big positive numbers (e.g., 1 million and 2 million) and if the values are very close, you know that it’s likely because the graph has a horizontal asymptote. The y value you get will also be the equation of the asymptote (y=). You can then do the same thing with two large negative numbers.

Demo

Below is a table of our function f(x) approaching our horizontal asymptote but never reaching it:

| f(x) | result |

|---|---|

| f(1000) | 0.001 |

| f(2000) | 0.0005 |

| f(3000) | 0.0003333 |

| f(4000) | 0.00025 |

| f(5000) | 0.0002 |

| f(6000) | 0.00016666 |

| f(7000) | 0.0001428 |

| f(1000000) | 0.000001 |

As you can see from the table, our graph approaches zero as x approaches infinity, but we are never able to reach our asymptote at infinity.

The More Professional Way

If you are in school like I was when I learned this, you may have a teacher that will not like the above solution. They may say that no matter how many points you plug in, it was merely a coincidence that all the points pointed (pun intended) to the function having a horizontal asymptote. If so, follow the instructions below:

You take the rational function they give you, say for example . You identify the highest power of x—in this case it is to the two (squared). You then rewrite the equation ignoring any factors that aren’t raised to the second power and we get the following: .

From this we can see that as x becomes a very large positive or negative number, y approaches zero. Thus we have identified the equation of the horizontal asymptote as being zero. This can also be written as the limit as x approaches ±∞ = 0. You can verify this by graphing our function and zooming out a lot.

There are 3 key scenarios using this method:

- A bigger power on top: In which case no horizontal asymptote will exist, as the function will not approach a fixed value as it approaches infinity. This may be a non-linear asymptote (such as a slant one) because the numerator will be growing faster than the denominator.

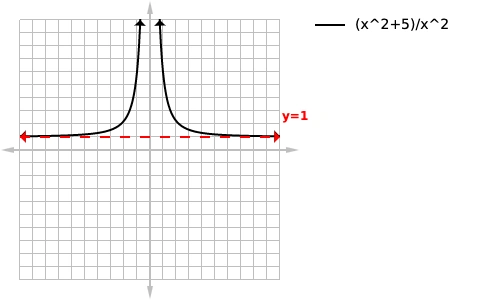

- Equal powers: In this case the horizontal asymptote will be the fraction of the coefficients between the two factors with the highest power (in this case there must be at least one factor present that is of a lower power).

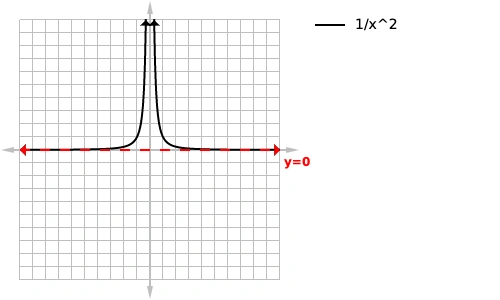

- Bigger on the bottom: In which case the function will have a horizontal asymptote of zero as the denominator will grow faster than the numerator.

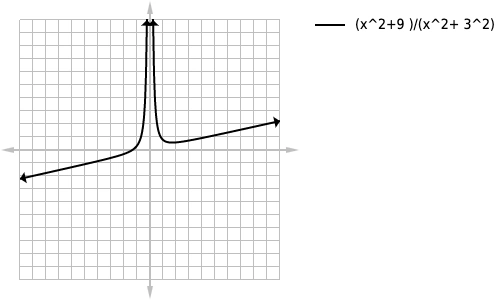

Example 1

This question is a model of our second scenario, “equal powers.” 2 is obviously our largest power here, so we can simplify the equation to . And since both the numerator and denominator have equal powers, the equation of our horizontal asymptote will be the fraction of our coefficients: , which simplifies to y=1.

Example 2

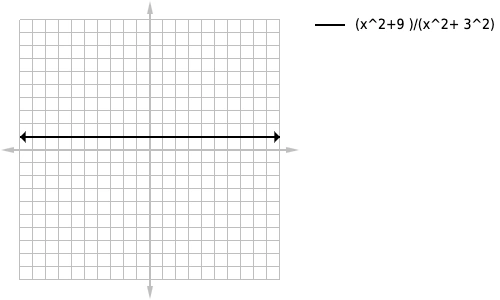

Naturally you may think that this is the “equal powers” situation and want to identify the highest power then cross things out like I’ve told you to before. But you would be wrong, because this equation expands out to , which simplifies to 1, which is a horizontal line. And horizontal lines can’t have horizontal asymptotes.

Example 3

Because the numerator has a larger power than the denominator, we can immediately recognize that the graph will not have a horizontal asymptote as the numerator will grow substantially faster than the denominator as we approach infinity. We will not have a horizontal-looking line as we zoom out on our graphing calculator.

We could also recognize this by using the method I mentioned about crossing out all factors that are not to the highest power. We would be left with: .

And since the numerator will grow with x and the denominator will not since it’s fixed at 1, we can tell that the graph will trend upward as x goes toward infinity.

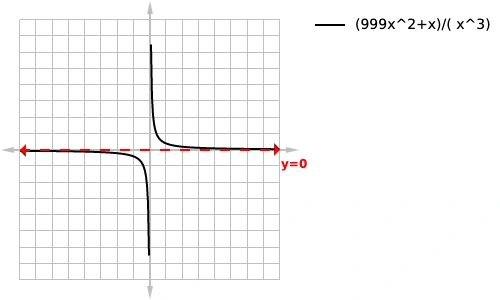

Example 4

This one should be easy for you. Because the denominator has x to a greater power than the numerator, we can immediately identify the horizontal asymptote as y=0.

We could also use the crossing out method I taught earlier. By removing all factors with a power less than 3 we are left with: .

And as x increases we get closer and closer to 0, making the equation of our horizontal asymptote: .

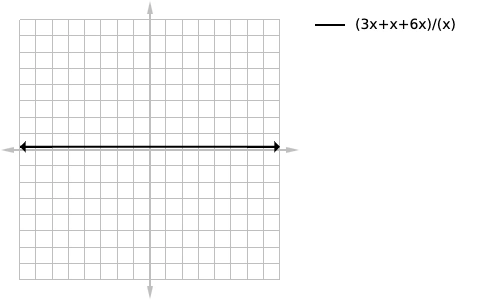

Example 5

This one I just threw in for fun. It’s another horizontal line because when simplified you get: , which is in itself a horizontal line, and horizontal lines can’t have horizontal asymptotes.

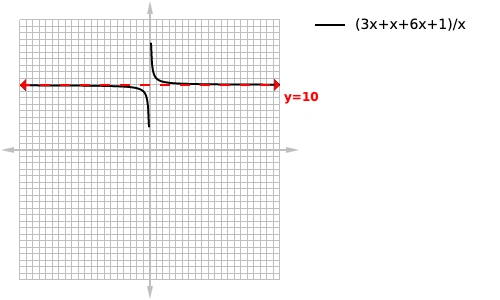

Example 6

I know this one may look very similar to the last example, but when simplified you get .

And that additional fixed factor of 1 in the numerator is what makes this function have a horizontal asymptote, as the relevance of that one to the final product becomes less and less significant as x increases. Since we have equal powers, we know that our horizontal asymptote will be the fraction of our coefficients, or 10.

Example 7

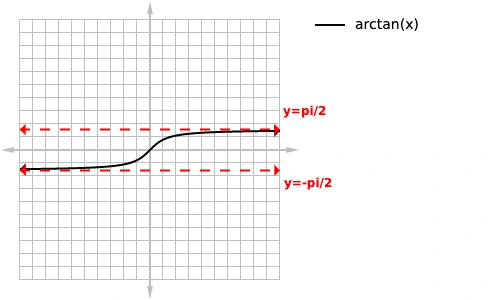

Which can also be written as or “tan inverse x” or “arctan(x).”

This is a unique situation because it will have 2 different horizontal asymptotes: 1 as the equation approaches positive infinity and a different one as it approaches negative infinity.

Pro Tips

- There can be at most 2 horizontal asymptotes (one facing positive infinity, one at negative)

- Make yourself comfortable graphing

- If you have difficulty graphing, you can always fall back to drawing points and by using the table function on your calculator to generate points quickly

- The horizontal asymptote for positive infinity does not have to be the same as the one for negative infinity

- Horizontal asymptotes can always be represented using limits

- Horizontal asymptotes can be crossed a fixed number of times

- Use a graphing calculator/desmos.com to verify your solutions

- Horizontal asymptotes can be irrational y values as demonstrated in our last example

- Don’t forget to verify that your function is not just a horizontal line in disguise

- Horizontal asymptotes play a big part in determining the end behavior of a function

THANKS FOR READING