An Introduction to Mathematical Limits

Sometimes we can’t find solutions to math problems because a solution either doesn’t exist (is indeterminate) but we can find a solution incredibly close from both sides and can see what our solution would be if it were to exist. Other times the limit of a point can exist but may not equal the function value at that point, i.e., . Another use case for limits is to determine end behavior of a function (limits at infinity), but that’s beyond the scope of this article.

A good example use case for limits is: . When graphed it would look like a perfectly straight line, right? But let’s say we were tasked with finding what x=0 was. If we were to plug in zero into our equation we would get , but therein lies our problem—a solution does not exist because zero is not in the domain of our function. is considered the indeterminate form. Through the use of a graph, we can kind of guess that the value is going to be zero, but that isn’t good enough for us (or viable on a test).

Understanding the Logic Behind Limits

The way that limits would approach our aforementioned problem is it would look at numbers very close to our desired one, which is zero in this case, and would make the assumption that whatever our very close numbers were going toward or approaching is the solution to our problem.

So for our aforementioned question we could plug in 0.0001 to give us . We could plug in smaller numbers closer to zero and we would see that our equation was approaching zero as x approached zero from the right, which could be written as (the plus means we are approaching our limit from the right and are trying numbers greater than our desired one).

We could then solve for our limit from the left by plugging in very small numbers less than our desired number such as -0.0001 and we would see that our limit as x approaches zero from the left is also zero, which can be written as .

Because the left and right limits approach the same value we can then merge these limits to conclude .

Now although we can never claim to know the value of x=0 for this equation, we can say that as we approach zero from both sides the limit is zero. For a solution to a limit problem to exist, direct substitution must lead to the indeterminate form of .

One-Sided Limits from the Left

A limit from the left is written in the general form: . Notice the “negative” exponent on the value we are approaching—that means that we only want to approach a from the left and that we will only test x values that are less than but very close to a.

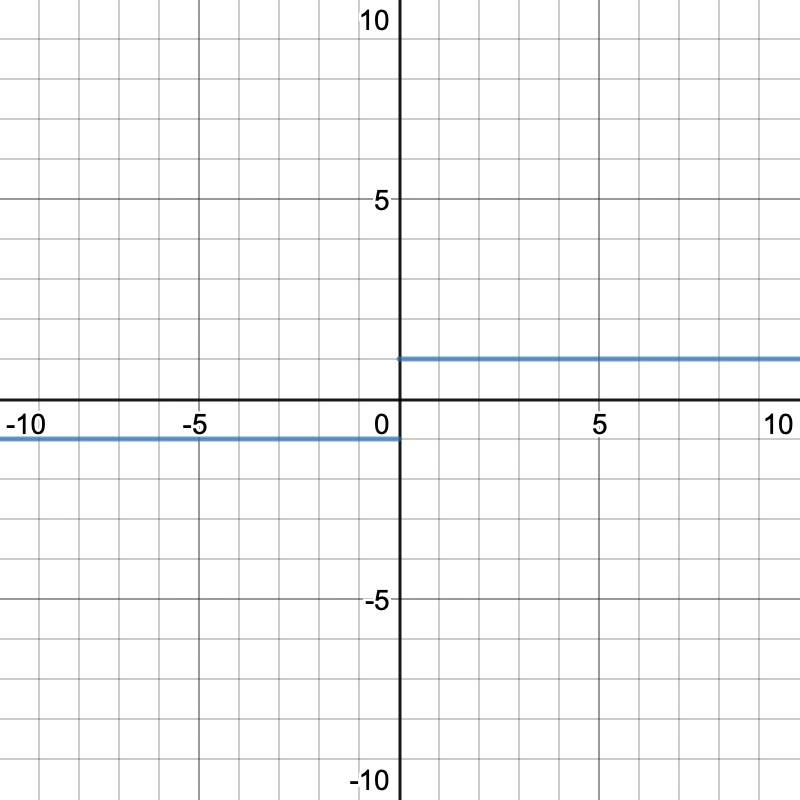

A very popular example of this is .

Our limit , but our two-sided limit does not exist. I will explain why below.

One-Sided Limits from the Right

A limit from the right is written in the general form: . Notice the “positive” exponent on the value we are approaching—that means that we only want to approach a from the right and that we will only test x values that are greater than but very close to a.

Continuing our example from above, our right-sided limit would be .

Two-Sided/Normal Limits

We can only say that the two-sided limit exists if both one-sided limits exist and are equal to each other, that is:

Continuing our example from before, we can say that does not exist because , which can be visualized better with a graph.

Limit Solving Strategies

Many different approaches exist for solving limits. When I was in high school I used a scientific calculator to plug in really close numbers from both sides to determine the limit, but that isn’t a “valid” approach according to most teachers—but is still a completely valid way of validating your solutions.

Direct Substitution

Sometimes you can directly plug your number into the equation and get a result. Beware that if this value is on the very edge of your domain there may be no solution to your limit.

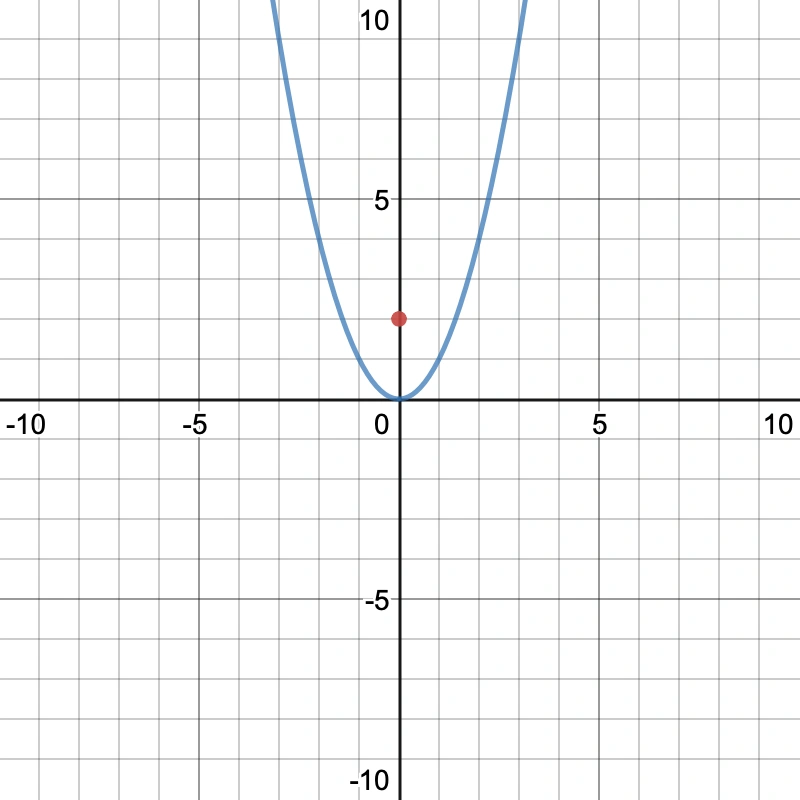

For example, let .

If we were to try and solve through direct substitution we would get zero, but some may argue that the limit does not exist as we cannot solve for a limit from the left as the function is not defined for any number to the left of (less than) zero. You should definitely clarify with your instructor about this.

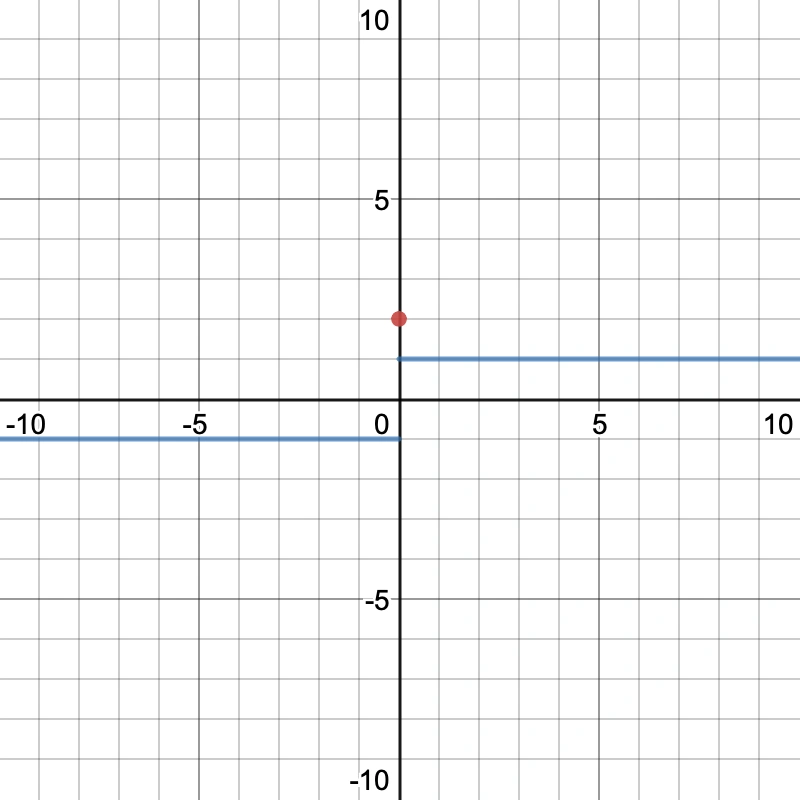

Another common issue with this method is when you plug into a function that looks like the following:

The issue here is that the limit does not exist as x approaches zero, but f(0)=2. So if you were to just plug in without verifying your solution you can get limits that don’t exist or are incorrect.

OR:

Here, the limit does exist, but just plugging in would give you the wrong answer.

Factoring

This is the most common method. It involves essentially removing the hole from the equation then directly substituting the value.

A simple example of this is .

If we factor the binomial we get .

We can then “cancel out” from both our numerator and denominator to get .

From there we can directly substitute to get the solution to our limit, which is -6.

Multiplying by a Conjugate

Sometimes you will get a question such as and you want to solve for the limit as x approaches 9.

So you can multiply by the conjugate divided by itself (which is essentially multiplying by one) to get:

Which simplifies to:

We can then “cross out” the common factor to get:

We can then substitute in the 9 to get as our limit.

Limits Approaching Infinity

These limits are only tested from one side and can only have one of 3 possible values:

- A fixed number for a horizontal line or asymptote

- Positive infinity for something going upward

- Negative infinity for something going downward

I would recommend reading my tutorial on horizontal asymptotes to better understand how to solve these.

Example 1

This one is fairly easy because the bigger x we plug in, we can see that x squared grows bigger, so we can say that .

Example 2

This one is fairly easy because we can just plug in: .

Example 3

This one does not exist because the two one-sided limits are not equal. From the left it’s negative one, from the right it’s positive one.

Example 4

This limit does not exist because it is a vertical asymptote. The missing value is impossible to factor out and direct substitution gives us , which is not the indeterminate form and will always be a vertical asymptote.

Example 5

This limit does not exist because it is a vertical asymptote. The missing value is impossible to factor out and direct substitution gives us , which is not the indeterminate form and will always be a vertical asymptote.

Example 6

As x is going toward negative infinity we can restrict our domain to x<0 and rewrite this as .

From here it should be fairly clear to you that one divided by a constantly increasing number will be zero. Another way to look at it would be , which isn’t technically mathematically correct but should make it more clear to you about why our solution is zero.

Example 7

This one starts with us pulling the common factor out of our numerator:

From there we can factor the numerator:

From there we can cross out the common factor to get our final solution:

Fun Use Case

Using your new found knowledge of limits you can now tell your friends you can solve (sort of) by defining a function . We can then take the limit of that as x approaches zero:

Pro Tips

- Limits to infinity can’t be evaluated from both sides

- Always remember to evaluate limits from both sides where possible

- Limits don’t always have to be indeterminate values of the function

- Limits are most commonly used to identify and solve for holes in a function

- Limits can only exist if they take the indeterminate form (a hole, ) or a solution when directly plugged into

- Remember to test your solution from both sides if you are directly substituting in

- Use a graphing calculator/desmos.com to verify your solutions

- Limits of vertical asymptotes are technically undefined/D.N.E (does not exist) but some people will still write them as

THANKS FOR READING